Exceedingly Real

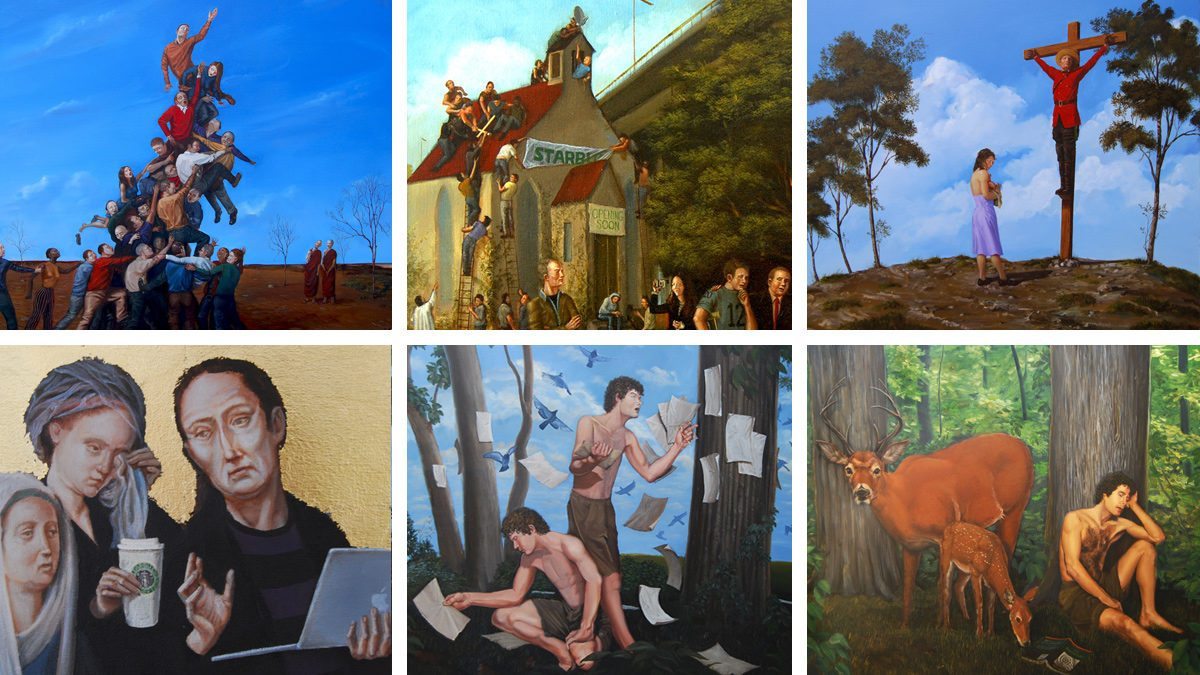

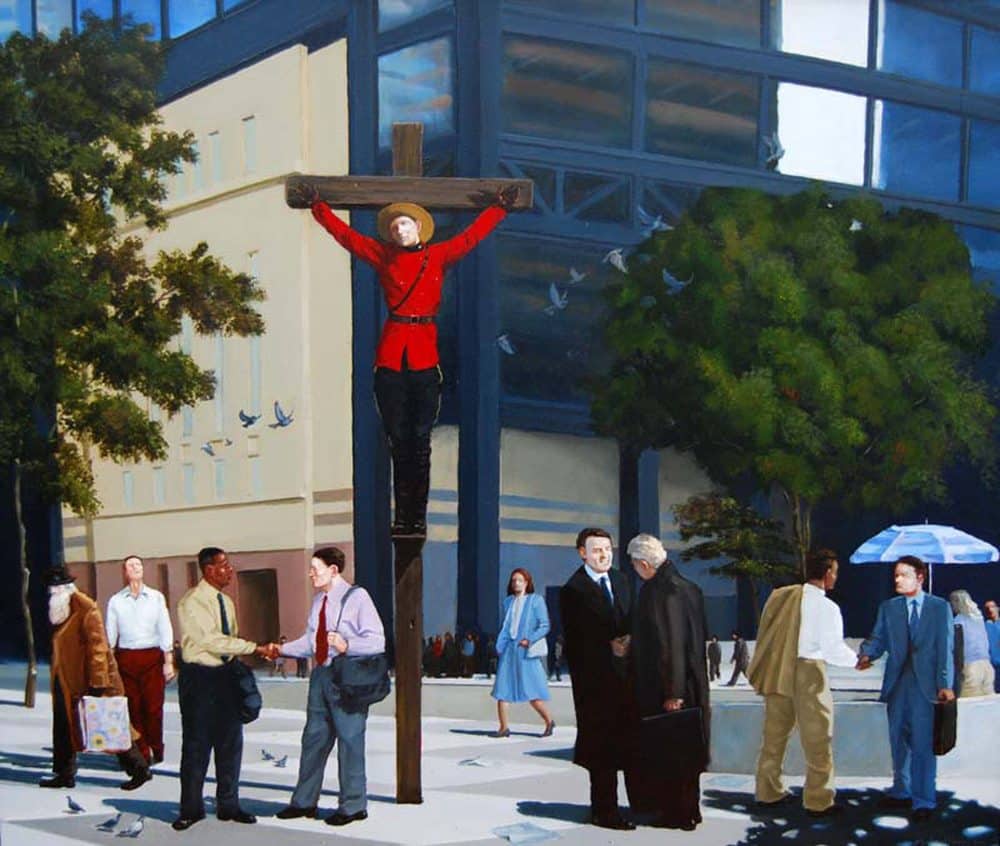

Michael Harris’ paintings and photographs deploy Realist idioms for integral expression.

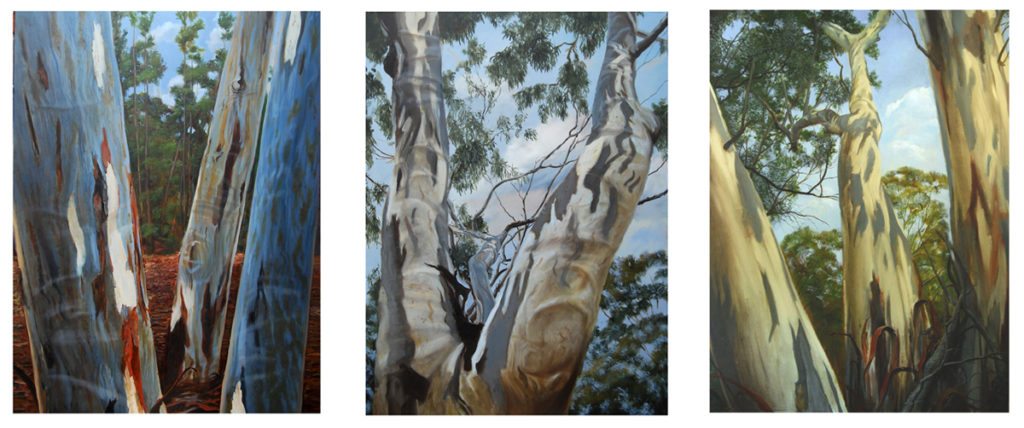

His landscapes are effectively transcendental: from Mist and Light’s dream-like radiant voidness; to Breathe’s abstracting blinding shine; to Force of Nature’s sublime vastness and disclosure of the uncanny wildness of nature.

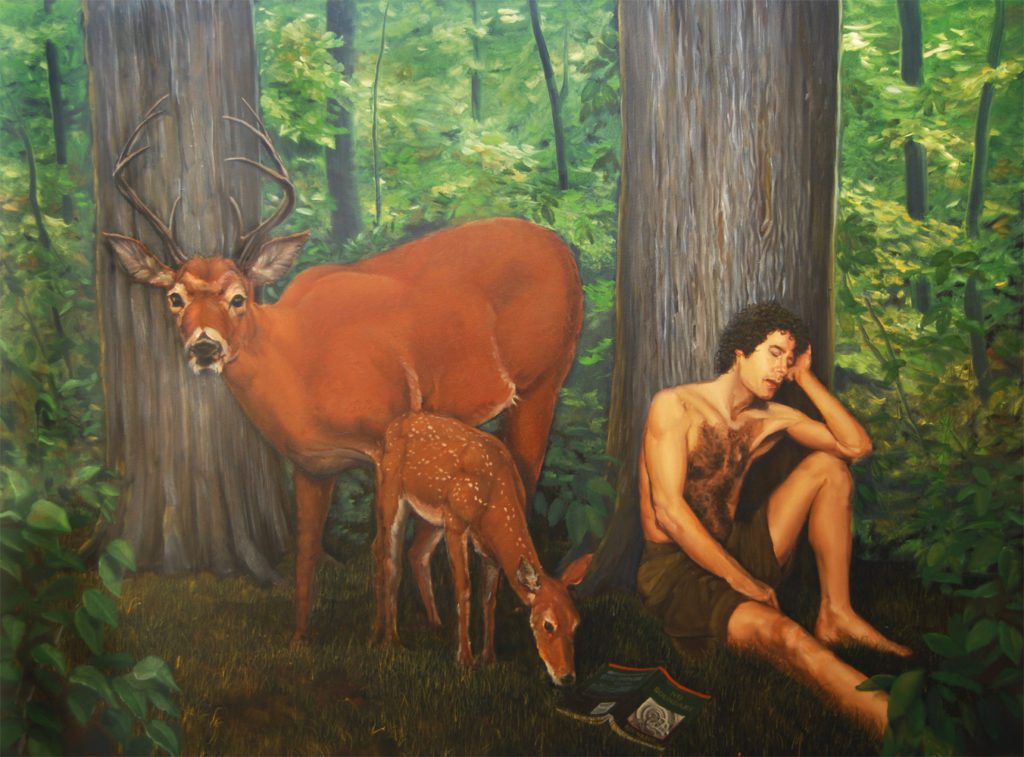

With the figurative works, Realist surfaces signify an integral robustness that invites multiple lines of interpretative questioning. In No Boundary a man leans against a tree, resting his head against his hand, apparently asleep. There is an open copy of Wilber’s early masterwork No Boundary (1979) nearby on the ground — as if he had just prior been reading that text and has fallen asleep into contemplation of the text. Seemingly unbeknownst to the man (a self portrait of the artist), two deer have wandered by, the young one noticing the book, the adult looking directly at us. What are we to make of the activities of these two deer? Does the young one see the book or, having a different anatomy, sense it via smell? Does this creature’s curiosity about the book have anything to do with its content? What too are we to make of the adult’s gaze meeting ours? And do these two sentient beings have access to the stateless state of “no boundary”?

The man is in a pose of inner absorption, attention withdrawn from the sensory into more subtle domains – a theme proper to post-medieval Western painting. In Lodovico Carracci’s The Dream of St. Catherine of Alexandria (c. 1593), St. Catherine rests her head on her hand while asleep, the object of her dream the appearance of Virgin, Child, and angels. The dreamer and contents of the dream are within the same pictorial space, have the same light source and general style, all of a this-worldly sensory kind; only the larger scale of the holy figures, the inclusion of the divine figures in and against a cropped circling aura of seraphim, and the bolder modeling of flesh differentiate the reality spheres of the dreaming Catherine (gross domain) from the holy beings (subtle domain). The gross-dreamer / subtle-dream boundary blurs: as if Christ is incarnating during dreamtime.

A century and a half earlier, from the 1430s, in paintings by Jan van Eyck — The Madonna with Canon van der Peale and the Rolin Madonna — the separation of gross from subtle and embodied seer from the visionary-seen is erased. In each painting a male donor is engaging in private spiritual practice, the holy figures in the scene being the visionary objects of this devotion. In both pictures the donor, holy figures, and setting are seamlessly of one style. The embodied patron has eyes open, as if the holy figures might be seen with the eye of flesh; while as holy figures appearing during spiritual practice they are properly disclosed via the eyes of mind/spirit (as in Renaissance theories of the faculty of fantasia). The holy beings are thus at once posited as sensory and as visionary. And this dual domain status extends to the patron and setting, given the uniformity of style throughout. The reality status of the representation is thus like a möbius strip flowing so rapidly between the gross and subtle domains that the realms become fused.

Let’s return now to Harris’ No Boundary. Like St. Catherine in Lodovico’s painting, the man is asleep with head in hand, his inner absorption keyed by the contents of the open text. And like the patrons in the van Eycks there is no spatial or style distinction that concretely differentiates reality realms. What are we then to make of the sleeping man in No Boundary? Might his inwardness go even deeper than the subtle domains of these Renaissance and Baroque paintings – the relaxing into and as what Wilber in No Boundary calls Unity Consciousness, the ground of All, and as such the formless source of the pictorial scene as a whole?

Harris’ paintings and photographs spark such questions, in the end evincing a Mystery that can neither be symbolically shown nor conceptually known, but only directly realized.

Michael Schwartz

From the artist:

“As an art form, painting has the potential to engage both artist and audience on multiple levels at once. I think a great painting is one that goes beyond the ordinary in each of these layers. With apologies to deconstructionists and abstractionists everywhere, for me this is particularly true of representational painting. The simple reason being that it contains within it more layers than abstraction. Everything that is “in” an abstract painting is present within a representational piece, but not vice-versa.

The first and often most powerful level that lights up in the viewer is what you might call the “WOW” factor. The immediate aesthetic apprehension of the piece that arrests the attention. It is the part that transcends words and analysis. Really, if you don’t hit this one…what’s the point?

The next layer that impresses itself upon the viewer is usually the “meaning” of the piece. This depends on the ability of the painter to convey his concept or idea effectively so that it resonates broadly in the minds of viewers. It’s the “Hey, that’s clever” moment.

The next level of depth that may reveal itself to the viewer is the skill with which the painter manipulates the physical materials themselves. Mastery of this level can range from the sublime handling of colour and light of Caravaggio to the sumptuous gobs of Van Gogh’s frenetic expression frozen forever in time and colour. It’s the “I can’t believe someone can do that”-ness of a painting. It can be alienating to many people when this level is so often dismissed by a post-modern art elite who emphasize concept or expression – sometimes to the exclusion of skill or technique.

In general, I would say these are the layers that are present in a great painting. From “WOW” to “we get it” to “how did he do that?”. I think this aligns rather nicely with the “I”, “We”and “It” domains of the Integral map. The painter is like a juggler of depth – striving to keep every ball in the air at once with each new canvas. All for the delight and wonder of the crowd.”

Michael Harris

About Michael Harris

Michael Harris is an oil painter, song-writer and world traveller from Toronto. He is self-taught, having never sought out formal training in art. Michael briefly studied graphic design in college following high school, but left after a few months to backpack through Europe. Seven months of immersing himself in the galleries and culture of Europe at 19 was followed by a year of travel in Australia at 21. At 24, to mark his transition to the ranks of professional artist, Michael took his paints and palette on his year long "trip around the world" - painting his way through Hong Kong, Thailand, Australia, Nepal, India, Greece, Turkey and the UK. Between trips, Michael honed his skills as a working artist; doing everything from painting reproductions for an international art company, to illustration, to portraiture and other private commissions.