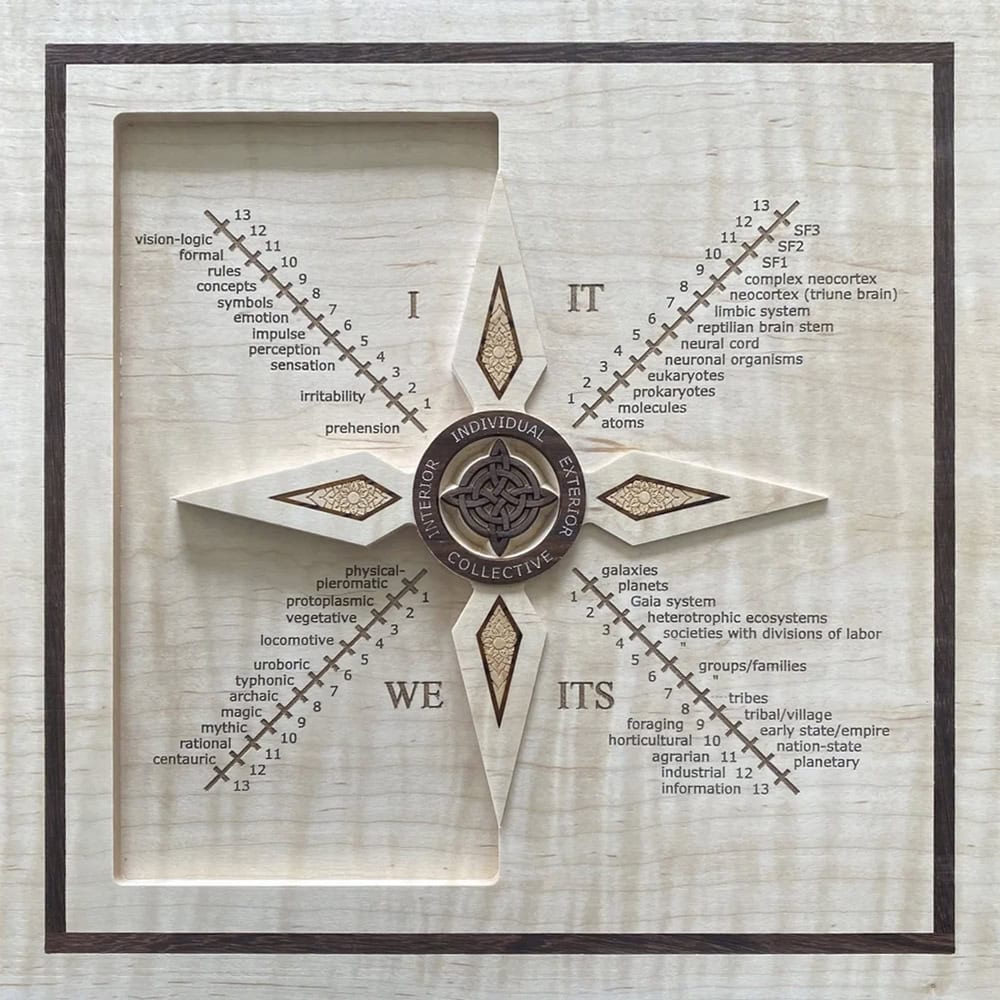

What Are the Four Quadrants?

“Truth was a mirror in the hands of God. It fell, and broke in to pieces. Everybody took a piece of it and they looked at it and thought they had the truth.”

—Rumi

A New Way of Seeing

Every argument you've ever had—every single one—has been a clash between different worlds that were all true at the same time.

Think about the last time you tried to explain something important to someone who just didn't get it. Maybe you were describing a profound personal experience, and they responded with statistics. Or perhaps someone reduced your carefully reasoned analysis to "just your opinion."

You were both right. You were both wrong. And you were both missing the bigger picture.

This maddening experience points to one of humanity's deepest challenges: we live in a universe that can be validly understood from radically different angles, yet we keep insisting that our angle is the only real one.

The mystic declares consciousness is everything. The scientist insists it's just neurons firing. The anthropologist sees it all as cultural construction. The systems theorist maps it as information flows. Wars are fought, relationships end, and institutions crumble because we can't see that these perspectives aren't contradictions—they're coordinates.

Ken Wilber's four quadrants model is essentially a peace treaty for the war of worldviews. It's a deceptively simple map that shows how every phenomenon in existence—from your morning coffee experience to the rise of civilizations—simultaneously exists across four irreducible dimensions of reality.

Master this framework, and you'll never see disagreements the same way again. You'll understand why your meditation teacher and your neuroscientist friend are both right about consciousness, why poets and economists both capture truth about love, and why every partial perspective you've ever held was both completely valid and dangerously incomplete.

The Coordinates of Experience

Imagine you’re trying to map the total terrain of reality — a comprehensive inventory of literally everything. Where do you even begin?

To map the entirety of existence, we start with two fundamental distinctions that cut through all of reality like cosmic axes.

The first cut is between interior and exterior — between what things look like from the inside versus what they look like from the outside. Your experience of tasting chocolate (rich, sweet, nostalgic) versus what a scientist sees through an fMRI (neurons firing in specific patterns). The meaning of a poem to you versus the ink patterns on paper. Your felt sense of love versus the oxytocin and dopamine flooding your brain. Neither view is more real than the other — they're describing the same event from irreducibly different vantage points.

Interior: the inner, subjective world of thoughts, feelings, meaning, and experience.

↔

Exterior: the outer, objective world of actions, behaviors, systems, and observable patterns.

The second cut divides individual from collective. Some realities belong to singular beings: your specific thoughts, your body, your unique perspective. Others belong to groups: shared languages, cultural worldviews, ecosystems, economic systems. Your personal values are individual; the culture that shaped them is collective. Your brain is individual; the evolution that designed it is collective. Again, neither is primary—individuals shape collectives while collectives shape individuals in an eternal dance.

Individual: the singular perspective — one person, one organism, one holon.

↕

Collective: the plural perspective — groups, cultures, systems, and networks.

Now here's where it gets interesting. When you cross these two distinctions — interior/exterior and individual/collective — four distinct quadrants emerge. Four fundamental territories of existence. Four irreducible perspectives on any event. Four windows through which the universe knows itself:

- The Interior of the Individual — what it feels like inside you

- The Exterior of the Individual — what others can observe about you

- The Interior of the Collective — the shared meanings and cultures we participate in

- The Exterior of the Collective — the systems and structures we inhabit

These are known as the Four Quadrants — and they are as basic to experience as north, south, east, and west are to navigation. Every moment of your life, every object you encounter, every idea you consider exists simultaneously in all four of these dimensions. Miss even one quadrant, and you're not seeing the full picture. Overemphasize one, and you fall into the partial blindness that has plagued human understanding for millennia. But grasp all four, and suddenly the fragmented world clicks into a unified whole — not by reducing everything to one single dimension, but by honoring the irreducible richness of all four.

These are not mere categories on a piece of paper; they are native perspectives of being-in-the-world, each enacting a distinctive worldspace with its own methods.

Let’s walk through these four perspectives in plain language, using examples you already know from your own life.

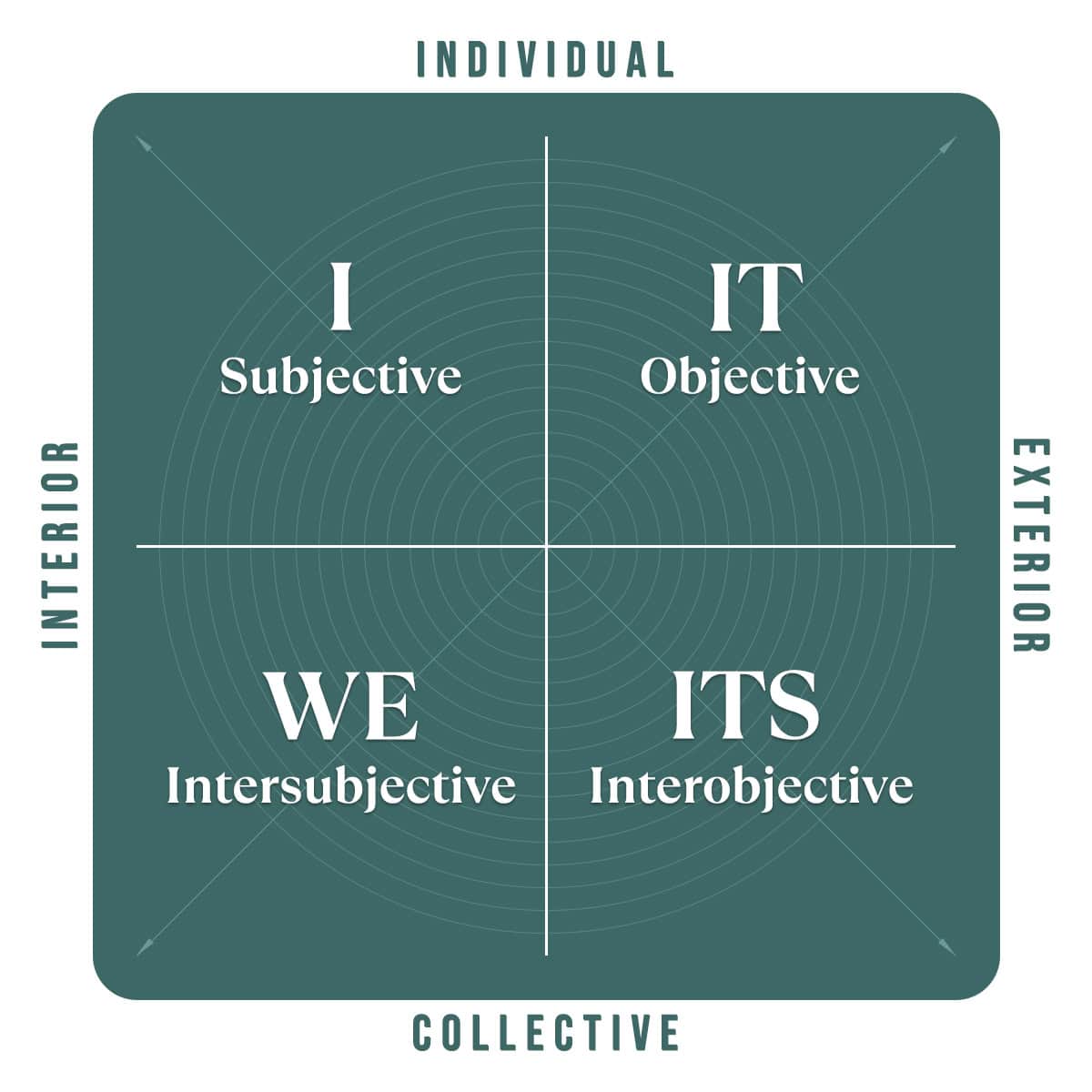

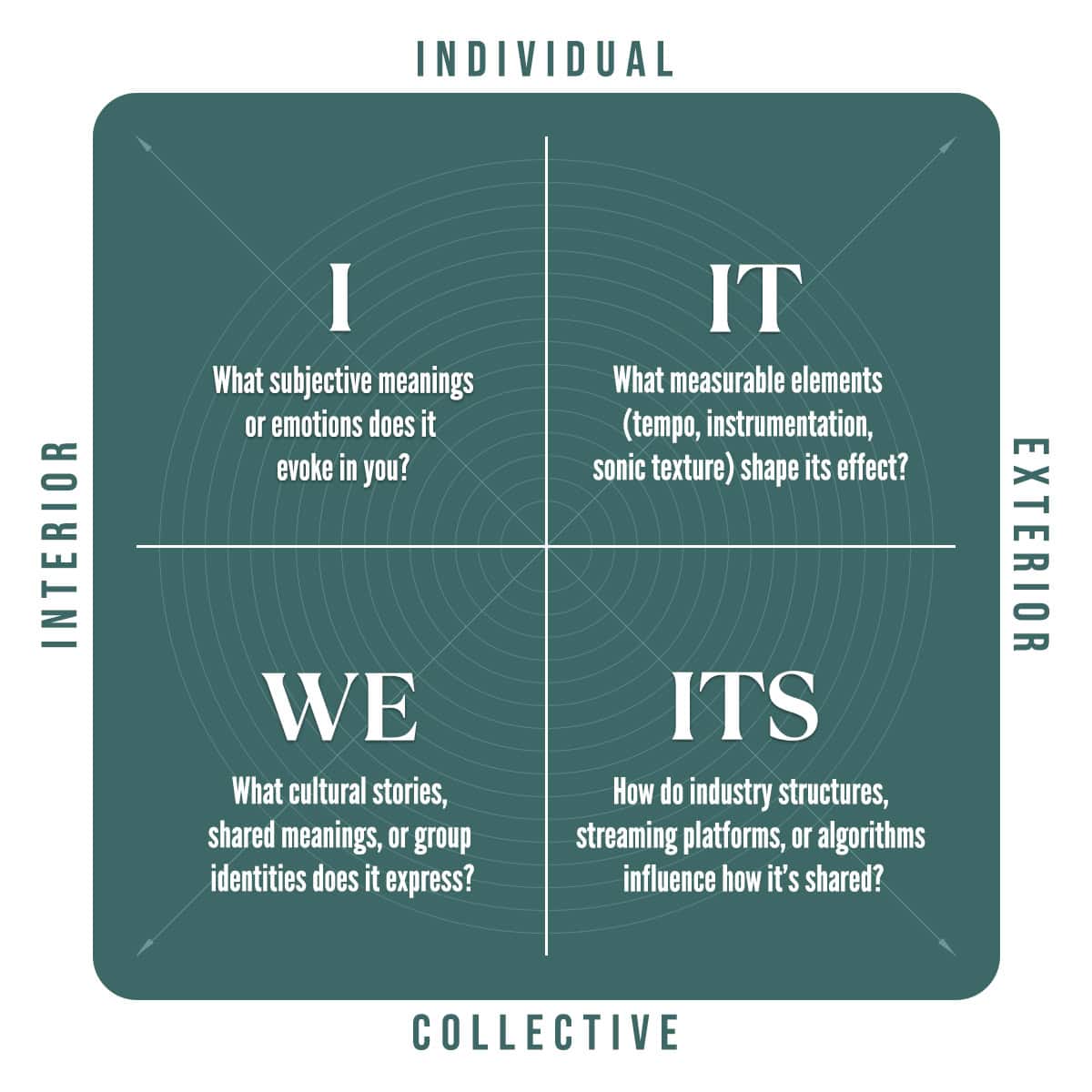

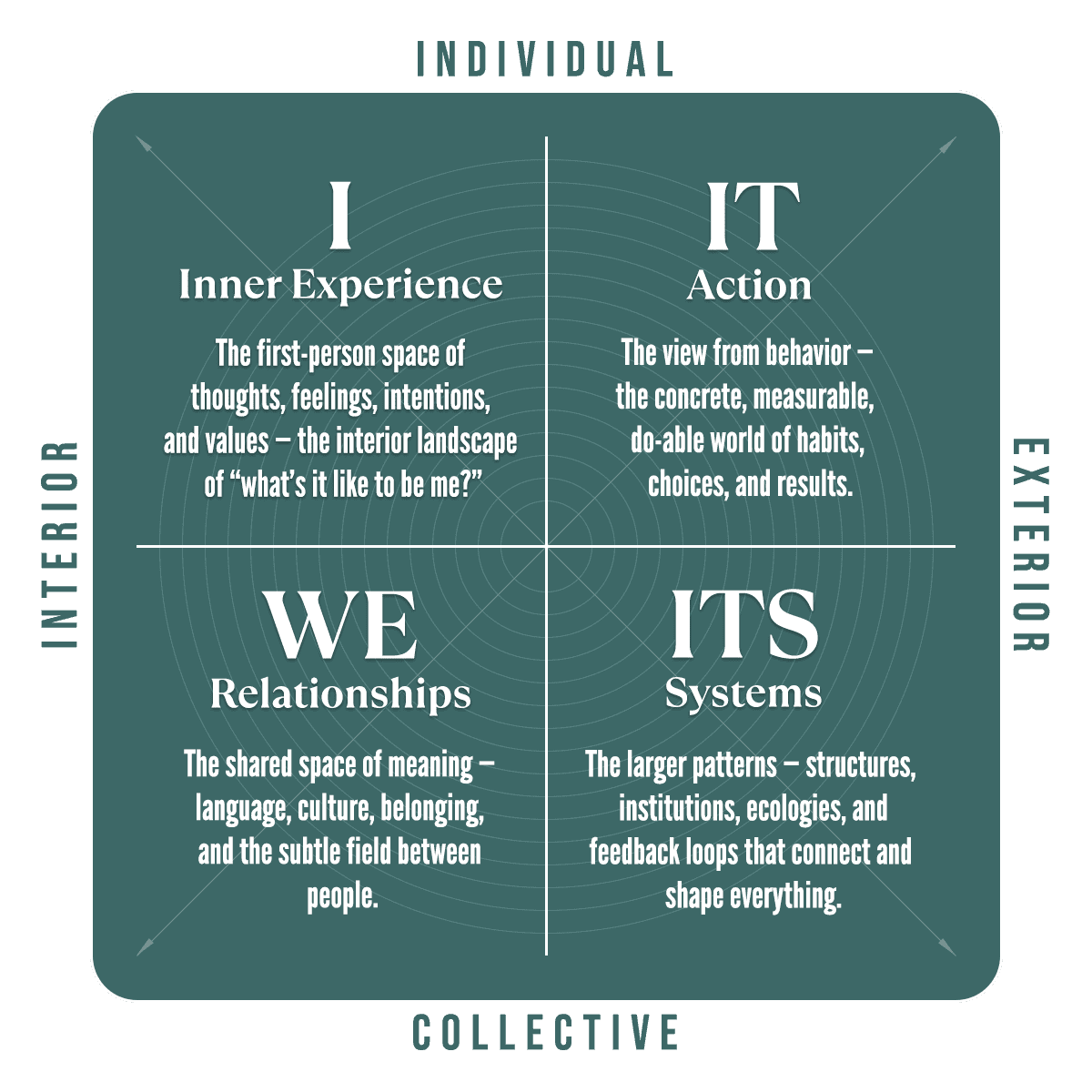

The Four Quadrants

The Four Quadrants

Upper Left: The “I” Space

(Interior Individual)

This is the subjective space of your inner world — the thoughts, feelings, intentions, memories, dreams, and awareness that only you can access.

It’s the realm of personal meaning, purpose, and first-person experience. When you say, “I feel anxious,” “I had a revelation,” or “That moved me deeply,” you’re speaking from here.

A poem lives here. So does prayer. So does the thrill of falling in love or the ache of heartbreak. It’s the part of you that notices beauty, intuits patterns, and silently talks to itself in the grocery store aisle.

Upper Right: The “It” Space

(Exterior Individua)

This is the objective view of you from the outside — your body, behaviors, physiology, and actions in the world.

It’s the realm of science and measurement: heart rates, hormone levels, neural firings, observable habits. It’s what someone else can point to and say, “Look — there.”

When a doctor measures your blood pressure, when a fitness tracker logs your steps, when someone notices you haven’t made eye contact all day — that’s the Upper-Right perspective in action.

Lower Left: The “We” Space

(Interior Collective)

This is the shared interior world we build together — culture, language, worldviews, norms, and stories. It’s the invisible fabric that makes a group feel like a group.

It’s why jokes land in one crowd, and fall flat in another. It’s why a tradition feels sacred to some and strange to others. It’s the pulse of belonging — or the sting of exclusion.

When someone says, “That’s just not how we do things here,” they’re speaking the language of the Lower-Left.

Lower Right: The “Its” Space

(Exterior Collective)

Finally, there’s the world of systems and structures — the networks, technologies, institutions, and environments that shape our lives from the outside.

Traffic patterns, economic policies, climate systems, digital platforms — these are all Lower-Right phenomena. They’re the reason your coffee costs what it does, your commute takes as long as it does, and your social media feed looks the way it does.

They’re often invisible until they break — and then they shape everything.

Another way to think about these four perspectives is through the pronouns we already use to describe reality:

The “I” space (Upper-Left) is subjective — the interior world of my own thoughts and feelings.

The “It” space (Upper-Right) is objective — the exterior world of things and behaviors we can measure.

The “We” space (Lower-Left) is intersubjective — the shared interior of culture, language, and meaning.

The “Its” space (Lower-Right) is interobjective — the shared exterior of systems, structures, and networks.

These four pronouns are the deep grammar of reality itself — four ways of speaking that reflect four ways of being. Every time we use “I,” “It,” “We,” or “Its,” we’re orienting ourselves within this fourfold space.

It’s one thing to understand these quadrants conceptually. It’s another to feel them directly. Try this short exercise:

- Upper-Left: Close your eyes. Notice what’s happening inside you — thoughts, emotions, sensations. What’s the tone of your inner world right now?

- Upper-Right: Open your awareness to your body. How are you breathing? What’s your posture? What physical signals are present?

- Lower-Left: Bring someone else to mind — a friend, a team, a community. Feel the shared space between you. What unspoken understandings live there?

- Lower-Right: Zoom out. Notice the broader systems you’re part of — your home, neighborhood, economy, digital infrastructure. What background forces shape your daily life?

All four dimensions were present just now — not as abstract ideas, but as lived realities. They are always here, always shaping your experience, whether you pay attention or not.

Why It Matters: The Cost of Partial Vision

When we lose sight of any quadrant, we don't just miss information — we create catastrophes.

Consider modern medicine's historic blindness to interior experience. For decades, doctors dismissed chronic pain patients whose suffering didn't show up on tests (ignoring the upper-left quadrant while fixating on the upper-right). Millions suffered needlessly. Only when medicine began honoring subjective patient experience alongside objective measurements did treatments for fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue, and countless "invisible" conditions finally emerge.

Or watch what happens when we ignore collective interiors. Tech companies design algorithmically perfect platforms (lower-right systems) that tear apart the social fabric (lower-left culture). Urban planners create efficiently engineered cities that become soulless wastelands nobody wants to live in. Educational reforms optimize test scores while crushing creativity and meaning. When we forget that humans live in webs of shared meaning, not just functional systems, our solutions become part of the problem.

The New Age movement often commits the opposite error—dwelling so deeply in personal consciousness (upper-left) that it ignores exterior realities. "You create your own reality" becomes a cruel joke when said to someone in poverty (lower-right systems), facing systemic oppression (lower-left cultural dynamics), or dealing with chronic illness (upper-right biology). Meditation alone won't fix structural inequality, policy alone won't heal trauma, and positive thinking alone won't cure cancer.

Even our most intractable conflicts often boil down to quadrant warfare. The religious fundamentalist and the militant atheist are both right about what they see and blind to what they don't. One sees interior meaning everywhere (left-hand quadrants); the other sees only exterior matter (right-hand quadrants). They're having different conversations while believing it's the same one.

This isn't inert philosophy — it's the root of why our solutions keep failing. Climate change can't be solved by technology alone (right-hand) without shifting consciousness and culture (left-hand). Mental health requires both neuroscience (upper-right) and depth psychology (upper-left), both individual healing and collective change. Every partial approach eventually hits a wall created by its own blind spots.

The four quadrants are a corrective lens for a fragmented world — a way to stop fighting over which piece of truth is the whole truth and start integrating the pieces into solutions that actually work.

Seeing Wholeness: Two Ways of Looking

The four quadrants reveal a profound distinction between what has consciousness, and what affects consciousness. All sentient creatures — from humans to birds to possibly even cells — actually possess four quadrants. They exist simultaneously as subjective experience, objective form, intersubjective relationships, and systemic nodes. But even things that lack interior experience can still be understood through the quadrant lens, by examining how they impact all four dimensions of reality.

This gives us two fundamentally different ways to engage with the quadrants:

- Looking as: Recognizing that sentient beings don't just "have" four quadrants — they exist as the living intersection of all four dimensions

- Looking at: Using the quadrants as a lens to analyze anything—sentient or not—and understand its full impact across all dimensions

🪞 Looking As: Seeing the Whole Person

Every sentient being simultaneously exists across all four quadrants. You aren't just a mind that has a body, participates in culture, and uses systems. You are the living convergence of all four dimensions.

You exist as subjective experience (upper-left) — the private stream of consciousness only you can access.

You exist as observable body and behavior (upper-right) — neurons firing, actions unfolding, the physical form others can see and measure.

You exist as an intersubjective being (lower-left) — enacted slightly differently by every person who knows you, woven into webs of meaning and relationship that partially constitute who you are.

And you exist as a systemic node (lower-right)—embedded in countless natural and artificial networks, from ecosystems to economies, your very perceptions and capacities shaped by the distributed intelligence of the systems you're part of.

This isn't metaphorical. You literally cannot exist without all four dimensions. Remove your subjective experience, and you're unconscious. Remove your brain, and you're dead. Remove your cultural embeddedness, and you have no language, no meaning, no identity. Remove your systemic supports, and you have no food, no air, no knowledge or context for existence. Every moment proves it: you are four quadrants arising as one.

🔍 Looking At: Seeing the Full Picture

But what about things that may lack interior experience — artificial intelligence, corporations, technologies, ideologies? While we don't believe AI has subjective experience (yet?), we can still analyze it through all four quadrants to understand its total impact on reality.

Take AI as an example. In the upper-left, we examine how it affects human consciousness—the fears it triggers, the creativity it sparks, the ways it changes how people think.

In the upper-right, we study how it alters individual behaviors and interfaces with our biology.

In the lower-left, we explore its cultural impact—how different societies interpret it, the meanings we project onto it, the relationships it mediates or disrupts.

In the lower-right, we trace its systemic effects—economic disruptions, energy consumption, geopolitical shifts, educational transformation.

This analytical power extends to anything: a policy, a pandemic, a work of art, a climate pattern. Even if something lacks interiority, it still creates ripples across all four quadrants of existence. The quadrants become a tool for complete understanding—ensuring we never miss the psychological, behavioral, cultural, or systemic dimensions of anything we're trying to comprehend or change.

From Fragmentation to Integration

If it feels like knowledge is splintered — that’s because it is.

Science broke off from philosophy. Psychology split from sociology. Politics fractured into endless camps. Culture wars rage over which kind of truth matters most: subjective or objective, individual or systemic.

But step back, and a deeper pattern emerges: knowledge has always moved from fragmentation to integration.

Newton integrated the “laws of heaven” with the “laws of earth,” showing that the same physical forces govern movement regardless of scale or location.

Maxwell revealed that electricity and magnetism were actually two aspects of a single electromagnetic field.

Einstein unified space and time into the fabric of spacetime. Then for an encore he showed how matter and energy are interchangeable expressions of the same underlying reality.

Quantum mechanics demonstrated that particles and waves are complementary descriptions of quantum phenomena.

The Standard Model integrated the electromagnetic, weak nuclear, and strong nuclear forces into a unified framework. And of course physicists are today searching for the final unification—a theory of quantum gravity that would weave all four fundamental forces, including gravity, into a single coherent picture of reality.

And all that is happening in just one single quadrant (the Upper-Right) in one single layer of reality (atomic and subatomic levels). Knowledge itself is constantly becoming more whole, more coherent, more integrated, and it’s not just happening within particular paradigms or schools of thought, such as physics. It’s happening across all paradigms, all fields, all known methods of generating knowledge.

Everything fits together. And we are finally beginning to understand how.

Everything In Its Right Place

These four perspectives are so fundamental that every mature field of knowledge eventually discovers them — even if it uses different names. But because most disciplines evolved in isolation, they tend to overemphasize one or two quadrants and ignore the rest.

Here’s how that plays out across a number of knowledge domains:

The Four Quadrants Across Multiple Fields of Knowledge

The Four Quadrants Across Multiple Fields of Knowledge

The more we learn to see the quadrants in each field, the less we get stuck in ideological battles and the more we can build bridges between methods, models, and worldviews.

What Is Your Native Perspective?

Each of us is born into a world far too vast to grasp all at once — so our minds do something brilliant: they find a home base from which to make sense of it all. This home base is your native perspective — the lens you instinctively reach for when trying to understand yourself, other people, and the world around you.

Integral theory describes four primary perspectives that are always motivating you and shaping every moment of your life: inner experience, action, relationships, and systems.

All four perspectives are always present, like the four cardinal directions on a map. But most of us have one that feels like true north — a familiar orientation we return to again and again. A second one often supports and strengthens it. And one or two may feel like foreign territory — the directions we forget to look, or even resist.

Becoming a Bridge

The world is growing more complex, and our old ways of knowing can’t keep up. We’re drowning in information but starving for coherence. We’re surrounded by truths but unable to hold them together.

The four quadrants offer a way forward — not as a final answer, but as a framework for integration. They help us navigate complexity without collapsing it, honor diversity without dissolving it, and hold multiple truths without losing sight of the whole.

And in a fractured world, the people who can do that — who can see whole — are the ones who will lead us forward. They are the translators, the bridge-builders, the connectors between worlds.

This is the beginning of that journey. Because once you learn to see reality through all four windows, you’ll never mistake a single view for the whole again.

And that’s where Integral thinking truly begins.

Next Steps

Explore how these four perspectives play out across the fields that matter most — from psychology and health to politics, art, and spirituality. Each is a laboratory for learning to “see whole.” And each is a doorway into the deeper path of integral practice.

This introduction is just the first step. The more you explore these primordial perspectives — in yourself, your relationships, your work, and the world — the more fluent you become in the grammar of reality itself. And from that fluency, a new kind of wisdom emerges — one capable of holding complexity with compassion, and diversity with depth.

Welcome to the Integral view.