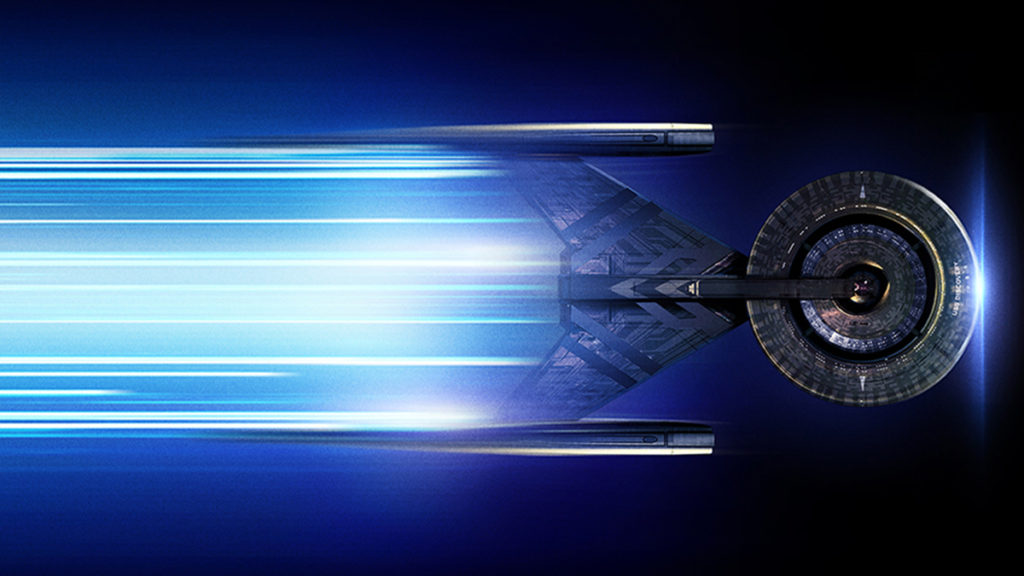

CBS has recently rebooted the 50-year old Star Trek franchise, returning the franchise to the small screen (where it truly belongs) for the first time since 2006 in its latest incarnation — Star Trek: Discovery.

One of the defining qualities of Star Trek has long been its immediate philosophical and social relevance to the world we live in today. This, of course, is what science fiction does best — it allows us to take a close and critical look at some of the most poignant and controversial challenges of our time by casting them into some far-future scenario, where it can be insulated by our suspension of disbelief and freed from the confines of our surrounding cultural and political biases, allowing fresh perspectives to arise.

After decades of dystopian blockbusters flooding our collective imagination, Star Trek offers some much-needed reprieve from our current apocalypse-obsessed entertainment culture. We’ve been buffeted by vision after nightmarish vision of our inevitable societal collapse, often brought back from the brink at the very last minute by one of our many modern superhero gods — unachievable projections of our most idealized selves.

But there are no superhero saviors in Star Trek, only ordinary human beings (and Kelpians, and Bajorans, and…) who only have their own skills, ethics, ingenuity, and teamwork to save the day. Star Trek is, if anything, something like “competence porn”.

Life imitates art, and one of my favorite things about Star Trek is seeing just how much of today’s technological and societal trends find their origin in this franchise — from cellphones to tablet computers, video chat, virtual reality holodecks, and universal translators, Star Trek has been ahead of the curve just about every step of the way.

I often talk about four major trends in our current bio-psycho-social evolution, which I have come to call “the four singularities” — and I can very easily trace each of these four trends to the Star Trek franchise:

- POST-SCARCITY: Star Trek offered us one of our very first visions of a truly post-scarcity world to ever appear in mainstream media. This is a particularly poignant influence for today’s world, when we as a civilization have evolved technologically to a point where viable post-scarcity strategies can begin to be considered for the first time in our history, headed as we are toward some version of a post-capital world.

- POST-HUMANISM: Star Trek has also given us at least two very different and very influential scenarios for our post-human future. One is found in Data’s Pinocchio story — the artificial life form who dreams of one day becoming a real live boy — whose search for humanity became the source of the very same humanity he was seeking. The other is found in the Borg, which has become an archetypal nightmare of technological dehumanization and fanatical collectivism at the expense of individuality.

- POST-IRONY: Star Trek is, if anything, a tremendously sincere and idealistic franchise, unhindered by the multiple layers of irony and detached cynicism that drenches so much of our current cultural output. It is refreshingly unashamed of its own corniness, allowing its central characters to hope, to aspire, to care, and to grow beyond the cynicism and detachment of our postmodern politics of “cool”. Our current “post-truth” madness is an inevitable result of our failure to achieve a genuine post-ironic culture, and Star Trek consistently offers a beacon of authenticity for us all to aspire to.

- POST-METAPHYSICS: It is common knowledge that, for the majority of its run, Gene Roddenberry had a very strict “no God” rule that he strictly held the showrunners to — despite creating a universe with decidedly god-like intelligences, which gave rise to one of the series’ greatest lines from one of its all-time worst films: “What does God need with a space ship?” The idea was that, in this future timeline, humanity had learned to overcome the backwaters of mythic, black-and-white, us-vs.-them thinking, allowing reason and humanitarian morality to illuminate the cold empty blackness separating civilizations. Interestingly, this resulted in a science fiction ethos that was in many ways more spiritual than the world of religion that it left behind.

But really, the soul of Star Trek isn’t optimism or idealism or a roadmap to utopia. All of those are byproducts of the actual moral core of the series: exploring post-conventional morality, and owning the consequences of decisions made from that stage.

There is a scene in Star Trek: Discovery where Michael Burnham, the talented and cocksure first officer, has to make an impossible decision — either betray herself, her career, and her captain, or else risk allowing her closest friends and crewmates to be destroyed by a far more powerful enemy.

It’s a classic no-win situation. Starfleet cadets have a name for this — the “Kobayashi Maru” — a simulated rite of passage for many who train at the Academy. But Michael didn’t go to the Academy. She was raised on an alien world by Vulcans after her human parents were killed decades ago. She had never faced a no-win decision quite like this, where the only available choices are equally terrible and either road leads into darkness.

She knows what she needs to do. She excelled at her training on Vulcan. She knows how to control her all-too-human emotions and fears. She makes her choice. She knows it is the only logical choice, and the one she least wanted to make.

She chooses wrong.

And not only does she make the wrong choice, but the consequences are far more severe than she imagined. It was her own real-life Kobayashi Maru… and she failed.

This is classic Star Trek. At its core, beneath its tireless optimism and corny idealism and geeky technobabble, Star Trek is a show about moral choices. Particularly the really difficult ones, when the most important rules must be broken, when our most meaningful relationships must be betrayed, when our own integrity and dignity and principles must be sacrificed for the needs of the many.

“Star Trek offers a far more stirring vision of humanity’s greater potential by extending the moral arc of the universe far ahead in space and time.”

It’s one of the things Star Trek does best: exploring moral choices from a post-conventional stage. Put another way, it’s about having a very strict Prime Directive, and understanding why it must never ever be broken — and then knowing exactly when you need to break it.

Post-conventional morality means finding the greatest depth for the greatest span — a prime directive if ever there was one. Take these sorts of post-conventional moral decisions, toss in a Vulcan or Klingon or two (and hopefully an Andorian, I love those guys) and you’ve got yourself a recipe for some good old fashioned Star Trek.

When the original Star Trek series first aired in 1966, America and many other parts of the world were in the midst of enormous cultural and social disruption. Technology was advancing at an alarming and unprecedented rate, while the fabric of society was being stretched and re-stitched by civil rights movements, political unrest, and global conflict. Everything was better than ever, and yet the world felt like it was resting on the edge of a bat’leth.

And then along came Star Trek, arriving at the perfect time to counter the tensions of the era, offering a far more stirring vision of humanity’s greater potential by extending the moral arc of the universe far ahead in space and time.

And now Star Trek has returned once again, offering us a new window into our possible future beyond the dystopian cyberpunk fever dream we seem to find ourselves in. Star Trek has always held a mirror to our own social inertia, and Discovery is no different, exploring the virtues (and consequences) of “infinite diversity in infinite combinations” just as these same values are under assault here in our own mirror universe.

“The show invites us to set aside our cynicism, to renew our trust in empathy and logic, and to allow ourselves to elevate our gaze and expand our dreams to a galactic scale.”

This incarnation of Star Trek is in many ways a bit more mature than its predecessors, more willing to examine its character’s flaws and the consequences of their failures. It is also possibly the most beautiful show I have ever seen on television. Sure, the Klingons look a bit different now, causing some long-time fans to furrow their forehead ridges — but the set design is incredible, the costumes are amazingly intricate, and the visual effects are absolutely mind-warping.

Most importantly, the moral heart of the show remains very much in place. Everything we love about Star Trek — the awe-inspiring technology, the uplifting visions of our post-scarcity future, the never-ending search for new life and new civilizations that, with any hope, may one day end up being our own — all of these are wrapped around the moral core of Star Trek, without which everything else falls apart into the vacuum. And just as it did 50 years ago, the show invites us to set aside our cynicism, to renew our trust in empathy and logic, and to allow ourselves to elevate our gaze and expand our dreams to a galactic scale. This a new Star Trek for a new generation, and it could not have returned at a better time.

Star Trek: Discovery is available to stream on the CBS All Access app, and on Netflix outside of the U.S.

Originally published in EVOLVE Magazine.

About Corey deVos

Corey W. deVos is editor and producer of Integral Life. He has worked for Integral Institute/Integal Life since Spring of 2003, and has been a student of integral theory and practice since 1996. Corey is also a professional woodworker, and many of his artworks can be found in his VisionLogix art gallery.