Integrating the Three Eyes of Awareness: Smith’s Aesthetic Gift

[With regard to a painting] there appears a ‘visible’ to the second power, a carnal essence or icon of the first. It is not a faded copy, a trompe l’oeil, or another thing….For I do not look at it as one looks at a thing, fixing it in its place. My gaze wanders within it as in the halos of Being. Rather than seeing it, I see according to, or with it.Maurice Merleau-Ponty, “Eye and Mind”

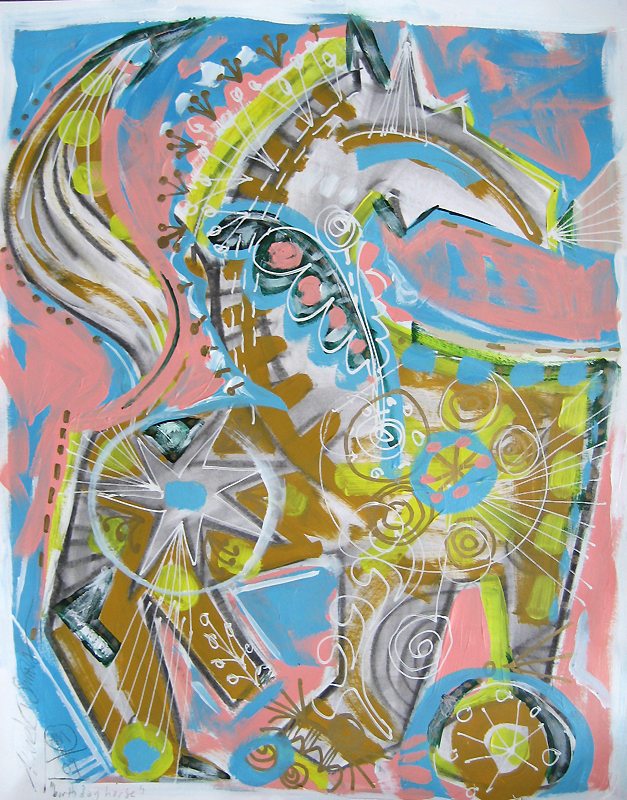

As Merleau-Ponty advices, we do not see a painting as we see a natural object, but see according to the painting—the work of art inviting, guiding, and structuring the way we see. Which brings us to Mark T. Smith’s rich and extraordinary art, paintings which show us how to see in an integral way; his art doing nothing less than modeling the integration of the three eyes of awareness: flesh, mind, and spirit.

What are the “three eyes of awareness”? They are the three principal modes of human knowing: the eye of flesh disclosing matters of sense (what we see, hear, taste, touch, and feel); the eye of mind disclosing more subtle modes (thoughts, illuminating insights, intuitive imagery, etc.); and the eye of spirit disclosing the ground of Being (Spirit shining through form; non-dual Mystery itself). This spectrum of the sensible, intelligible, and transcendental is presented as a remarkable aesthetic unity in the art of Mark T. Smith.

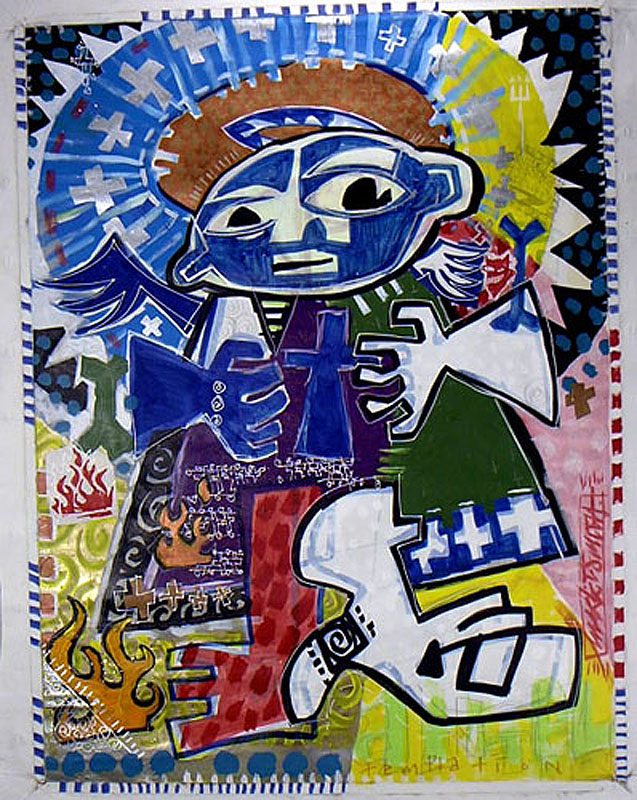

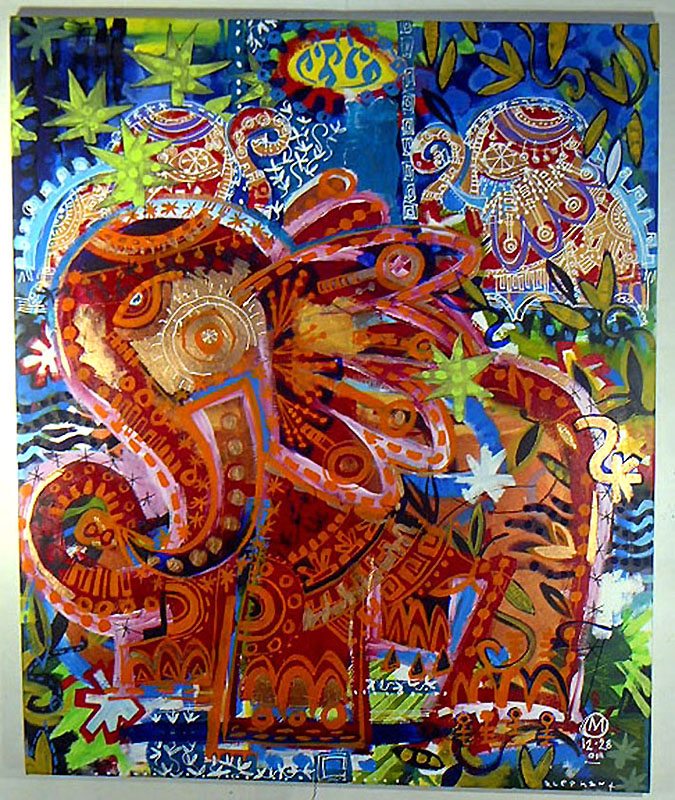

We shall focus on a single painting, Chaos Doghead, with what follows pertaining more broadly to the artist’s oeuvre.

The style of Chaos Doghead reverberates with a wide range of Modern idioms (cubism, abstraction), visionary-shamanic art (tribal, aboriginal), and mass culture itself (cartoons, signage). The depiction is at once artistically sophisticated and playfully accessible.

The discrete local elements—flat, un-modeled, eloquent shapes and patterns—are like the vocabulary of a fresh pictorial language expressing both personal (UL) and archetypal (LL) meanings. These sign-like elements help lift the imagery from “mere” sensory nature and plunge it deep into the symbolic, centering the painting’s object-content on the mental plane.

The composition dances in wild fecundity. Warm colors pop forward, neutral and cool colors recede. Surface and space are energized; a sensory display transfigured beyond mere eye candy. Colors self-radiate1 and shine the pervading beauty of the whole.

Most astonishing is that in looking into the eyes of the dog there is a sense of vastness, causal emptiness—a plane of Openness behind the rest of the pictorial world, a nameless Depth revealing and concealing Itself, Space shifting into flat opaque shapes. The mysterious and elusive eyes of a fierce Wisdom Teacher.

The object realm is centered in the symbolic (eye of mind), built up from discrete visual shapes and patterns laying on or close to the surface (eye of flesh), shapes and symbolic imagery shining in beauty, the trace of Spirit in form–a trace that finds its releases in the wisdom eyes of the animal teacher, a glimpse into vastness itself (eye of spirit).

Chaos Doghead is an exemplary aesthetic whole2. Whereas for most of us, in our everyday lives, only one or another of the three eyes of awareness comes to the fore—in Smith’s art we find a model of their profound integration, an aesthetic gift calling us to a more integral life.

Michael Schwartz

1 See “Modernism, Impressionism, and Color” (especially the discussion on Modernist color and its expression of self-luminous radiance.)

2 The philosopher Immanuel Kant, whose book the Critique of Judgment (1790) is widely regarded as the opening modern philosophical discussion on beauty, distinguished between nature and art in matters of aesthetics. For Kant, art alone is the result of a special set of operations of the human imagination, such that this creative process is guided by and centered in what he termed “aesthetic ideas.” Such ideas are not conceptual but regulative. They are for Kant the direct expression of Spirit. Such aesthetic ideas strive to organize the operations of the mind, in a way that does not happen as readily in our attending to nature and the everyday cultural world, such that ascent and descent, Eros and Agape, are woven, a weaving in integral terms of the three eyes of awareness. The resulting artistic creation uniquely embodies this imaginatively-empowered reconfiguring of experience. Viewing art requires then a kind of (pre)attuning to how such weaves are expressed in a given work – such that, following Merleau-Ponty’s, we come to see according to the artwork. We might say too that integral artists, like Smith, bring this creative-imaginative weaving of ascent and descent into a Fullness and Explicitness never quite seen before — almost as if Kant’s late 18th century theory anticipates the coming of early 21st century integral art (much as the philosopher Hegel’s writings on painting and color, dating from the early 19th century, seem to anticipate the coming of 20th century abstraction). On Kant’s notion of aesthetic ideas, see John Sallis, Transfigurements: On the True Sense of Art, 2009, chapter 4; and on Hegel’s anticipation of abstraction in painting, see ibid, chapter 5.

From the artist:

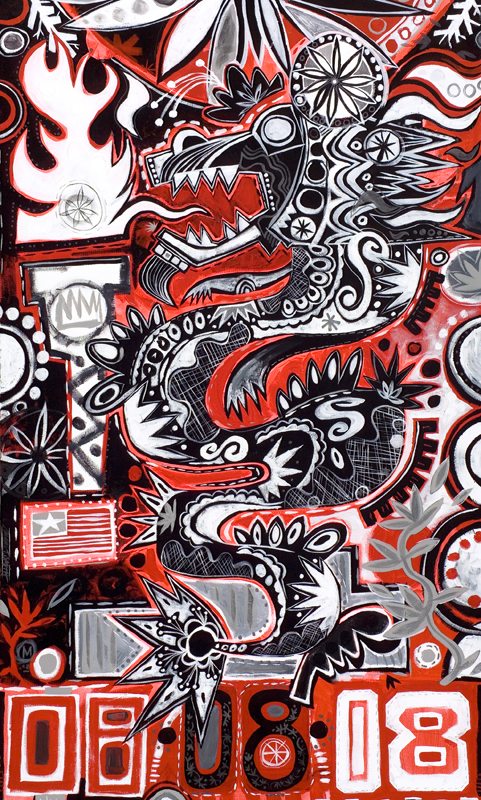

“My artwork has always been about the integration of the many influences that have crossed and continue to cross my life-path.

I have been influenced by the contemporary art world, balanced by constant exposure to the classics. My time in New York City gave birth to the visual language of my work—a language that embraces the traditions of draftsmanship, dedication to craft, observational drawing, and the myriad foundations of great works of art. At the same time my visual language was influenced by graffiti, hip-hop, post-pop, and the vast sea of advertising that is part of the everyday experience of our shared world. In short, the exposure and up take ran the gamut from pre-modern to modern to post-modern visual cultures, inclusive of the red, amber, orange, and green memes of expression, art dispersed throughout history in a wide variety of places and made for a wide variety of cultural and social purposes.

But stopping here would give us what many of the great Postmodern artists have given us—namely, a summary of what came before, but without an emergent ethos of its own save irony and deconstruction of past forms of meaning-making.

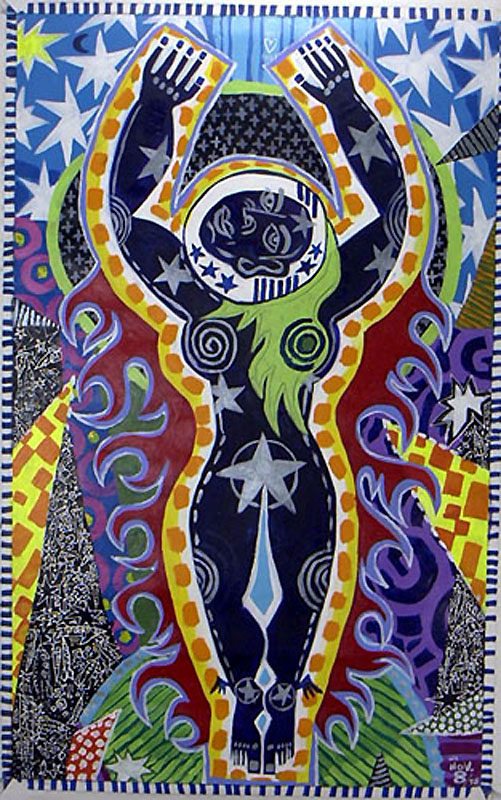

My work adds additional elements. One principle is the inclusion rather than derision of Spirit, while also honoring the postmodern foundation on which my work rests—a constructive rather than deconstructive postmodern practice.

With this combination of worldly and otherworldly elements, my artwork has grown and evolved into the recognizable forms it takes today. Upon close examination, the works yield a wide range of treasures. Some contain familiar Jungian universal archetypes, the symbols of cultures past, the influences of great western masters and the savvy of the images of the street. Other pieces are maps of travels and experiences, a visual diary of my journey as an artist and a reflection of my time and place in the ongoing evolution of art. This journey leads the viewer through that history, from the old guard to the revolutionary thoughts that shaped past generations of artists, and on through the present and into a future that embraces the best and most innovative in all these expressions.

As the co-called “high culture” art world has forsaken its connection with the general public and by and large forgotten its role as an ennobling force in contemporary life, I have spent the bulk of my career trying to re-establish that very link, maintaining the old audience and growing a new audience. This has been done by moving beyond expressions of irony as art, by arching backwards to include the great artistic insights that have come before, and by reaching forward into a future not yet seen or manifested.

The Eye of the Spirit looks out of its own face at its own evolution, and smiles.”

Mark T. Smith

About Mark Smith

Mark T. Smith is a celebrated American painter. He is best known for his colorful, complex paintings and his passion for the application of art into the fabric of everyday life. His artwork has been displayed everywhere from museums and galleries in the U.S. and abroad, to the walls of discerning collectors and the collections of celebrities like Jay Leno, Neil Diamond and Elton John.