Taking its roots in the European Enlightenment, and coming to fruition as a cultural and political force during the postmodern revolution of the mid 20th-century, feminism is certainly one of humanity’s crowning achievements. Early forms of feminism were faced with the difficult task of trying to define men and women’s roles in relation to each other, without access to an accurate model of human development and experience. As a result, feminist thought quickly branched out into many different schools of feminism — liberal feminism, Marxist feminism, radical feminism, libertarian feminism, ecofeminism, post-structural feminism, compatiblist feminism, etc. Each of these schools possesses its own set of underlying assumptions and overarching conclusions, while invariably leaving some crucial aspect of the human condition by the wayside.

Of course, none of these schools can be faulted for producing these incomplete maps of reality — quite the contrary, it is only because of the enormous body of data, research, and insight generated by these diverse vectors of inquiry that we can begin to pull the very best of these feminist schools together into a comprehensive view of sex, gender, and sexuality.

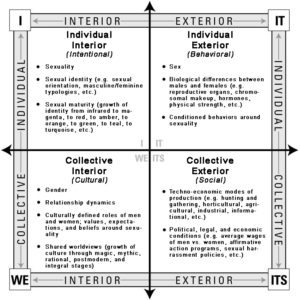

Here Ken offers a brief overview of precisely this sort of Integral feminism, taking into account the four major dimensions of human experience — personal, cultural, biological, and sociological — represented more fully in the graphic at the bottom of this page. He and Vanessa discuss how almost all preceding schools of feminism tend to focus exclusively upon only one or two of these dimensions, while dismissing data and perspectives from other dimensions of human experience, or else attempting to reduce these views according to their own partial presuppositions.

Taken one at a time, these conflicting schools of feminist thought seem to paint a chaotic and painfully fragmented mosaic of human sexuality — not too far off the mark, some might say. But when taken together, we begin to recognize our own intrinsic and mutual wholeness, discover new channels of intimacy that carve deep into our hearts; and witness entire worlds being drenched in ubiquitous beauty.

In 1991, feminist thinker Naomi Wolf wrote The Beauty Myth, a book that has been regarded by some as a sort of “last word” on beauty from the perspective of feminist thought. Subtitled How Images of Beauty are Used Against Women, Wolf argues that women are often oppressed by Western standards of beauty, which she believes to be a sort of last line of defense by the male-instituted patriarchy to dominate the spirit, psyche, and sexuality of females everywhere:

“Beauty is a currency system like the gold standard. Like any economy, it is determined by politics, and in the modern age in the West it is the last, best belief system that keeps male dominance intact.”Naomi Wolf

The Beauty Myth was a highly influential book within feminist circles, and has made significant contributions to the discussion of female beauty — particularly its culturally-constructed nature, its dependence upon male standards of beauty, and its impact upon just about every sphere of daily life. However, we might disagree with some of her larger conclusions, many of which are the result of some important dimension of sex, gender, and sexuality being collapsed, confused, or left out of the picture entirely. For example, though there is certainly a very strong culturally-constructed piece to our conceptions of beauty, it is by no means the sole factor, as Wolf seems to maintain — there are at least three other broad components to our definitions of beauty, including biology, developmental psychology, and techno-economic systems; and leaving any of these out is to dishonor the full complexity of male and female relations.

The Myth of Oppression

Considering that one of the central motives of feminist thought is to help women become more comfortable with their own bodies, these sorts of partial definitions of beauty have instead created more tension between women and their relationship with their physical form. To many feminist thinkers, any participation with today’s notions of physical beauty is seen as self-centered, shallow, and superficial — that is, putting on lipstick is just another form of surrender, admitting guilt-ridden subservience to a patriarchy that only seeks to dominate and control women through her sexuality. While this may sound like a fairly extreme caricature of feminism — and in many ways it is — it nonetheless remains an active sentiment within ongoing discussions of feminism and beauty, much to the frustration of women and men alike.

This brings us to one of the most universal and fundamental misconceptions in virtually all of feminist thought, what we might call “the myth of oppression.” As Ken points out, for one group of people to be truly oppressed, chances are that at least one of three possibilities is true: they are either dumber, weaker, or fewer in numbers than their oppressors. It is doubtful that we could find any sane person, male or female, who would suggest that women have ever fallen into any of these categories — and yet the myth of oppression lives on, a grim parody of the real oppression that men and women have both experienced throughout our shared history.

It is crucial to emphasize the following: though we may find it necessary to reframe our popular conceptions of male/female oppression, debunking the myth of women as perennial victim, at no point are we diminishing the very real experiences of oppression women encounter every day, all over the world. At every moment women are being demoralized. Her identity is being commodified, packaged, and sold for a quick profit. Her sexuality is either being forced upon her or ripped away, her soul ravaged by senseless acts of physical, emotional, and spiritual abuse. There is no denying that oppression exists in this world, that countless instances of exploitation and inequity persist to this very day, and that women are too often the victims of this oppression. It is enough to obliterate any man’s heart, if he were to open himself to the full severity of women’s suffering, if even for just a moment. And it is clear that men everywhere need to recognize these genuine instances of violence, find a way to collectively “man up” and take more ownership and responsibility for his gender’s behaviors, and begin to consciously redefine the male identity as women have been doing for generations.

But when trying to identify the source of this oppression, we must be careful not to allow ourselves to get swept away by the difficult emotions surrounding male/female oppression, or succumb to the glib oversimplifications presented by so many feminist thinkers: namely, the popular narrative that human history is one giant plot concocted by men to keep women under his thumb. Make no mistake, men and women are both oppressed, by ourselves, by each other, and by the forces of history. The dreaded patriarchy and all it is associated with — the sharp divisions between labor, gender roles, sexuality, temperament, etc. — men and women have created this mess together, out of sheer necessity of human survival, and both suffer under its weight. Thus, a comprehensive approach to feminism would not frame the issue as a woman’s struggle to escape her historical oppression by men, but as both men and women together struggling to escape the oppression of history itself.

Beyond the Male Gaze

There is no better barometer of a culture’s depth and sophistication than its art. Our highs and our lows, from the pinnacles of achievement to the pits of depravity — all of this finds expression in the music, the visual art, the literature, and every other act of creativity, echoing the living heartbeat of a culture. In many ways our art is a mirror, reflecting our beauty, our blemishes, and our biases back to us. But art is not inert — it lives and breathes through us, influencing our values and inspiring our virtues, unconsciously carving meaning from the cold granite of experience.

Our identities are intimately molded by the sounds, visions, and scripts that surround us. These identities that are often bound by the creative zeitgeist we are born into, placing symbolic limitations upon whom we can or cannot become. When we run out of reference points, we run out of meaning. And when we run out of meaning, we rub against our own sanity.

This is precisely what makes an evolutionary view of art so fascinating. Throughout history, developing cultures have inevitably bumped their heads upon the ceiling of what can and cannot be said, forcing them to say new things — to create new reference points, new formulations of meaning, new reflections of beauty, goodness, and truth. In these moments, the true genius of humanity comes alive — new worlds are born, new languages enacting new perceptions and experiences, all drawn from the same limitless creativity that ignites entire galaxies in the inky black of space.

We have seen exactly this sort of creative advance into novelty in the past several decades, particularly around the still-emerging feminist movement. Armed with the newfound languages of pluralism, postmodernism, and liberalism, women everywhere began en masse to deconstruct the identities that have been handed to them by culture — especially those aspects of identity they felt were being imposed upon them by men — cutting to the heart of many of our ideas about art. Not just the content itself, the form and function we can immediately see, but all the invisible elements as well — the unseen biases, assumptions, and perspectives which, over time, become the unquestioned substrate of our relationships to reality.

One of the most powerful critiques to emerge from feminist thought is the deconstruction of what is known as the “Male Gaze.” Originally introduced by Laura Mulvey in her essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” the Male Gaze is used to describe what is perceived as an asymmetrical power relationship between viewer and viewed, gazer and gazed, in which men impose objectification onto women. Stepping beyond the obvious content of an artwork, this critique questions both the context of the piece as well as the perspective from which it was created — challenging not just what is in the text, but how the text is presented. Feminists have long debated how they should relate to the Male Gaze — some feel victimized by it, some wish to deny it altogether, while others wish to understand and accept it as the natural expression of the masculine. Regardless of how women choose to shift their relationship with the Male Gaze, simply recognizing its existence did a great deal to open the art world to the feminine perspective, clearing a space for women to create their own new set of reference points — a new cultural mirror to more accurately reflect the depth and sophistication of the 20th- and 21st-century woman.

In several other discussions (most notably with Warren Farrell, John Gray, and David Deida) we have explored the idea of our sexuality growing through several distinct stages of maturity. Though there are many different ways to parse the spectrum of sexual development, a simple way to approach the question is to use a basic three-stage model:

- Stage 1 represents a period of cultural embedment, in which our identities are inextricably woven into our surrounding culture. Stage 1 is a playground of stereotypes — macho pigs and hysterical sheep, caveman clubs and baby machines. Caricatures, yes — but as every stereotype contains some element of truth or pattern of behavior, these are often not too far off the mark.

- Stage 2 is often accompanied by a transvaluation of male and female gender roles — for example, the idea that, if the playing field is to be truly even, women must have as much opportunity in the public sphere as men do. Here we find the masculinization of women and the feminization of men, each role attempting to define itself according to the other.

- Stage 3 represents an integration of masculine and feminine polarities in both men and women, emphasizing the need to become more of what you already are, rather than what you are not. Stage 3 sexuality focuses upon “cleaning up” many of the personal and cultural shadows leftover from Stage 1 and transcends the mind/body split that often occurs at stage 2, while inching ever closer toward greater clarity, presence, and radiance in men and women alike.

Here Ken identifies what he sees as the central dilemmas for feminism and gender studies as a whole — how to escape the endless cycles of blame and victim-hood (narratives that are usually diminished and often dismantled altogether in “Stage 3” maturity) and how to bring women into alignment with both her individuality and her relationships. This perpetual struggle between a woman’s autonomy and her communion has muddied the waters of sexual identity for decades, as both sides have been equally exalted and demonized, according to the current milieu of feminist thought.

If the Integral model can offer anything at all, it is a conceptual understanding of all the various components of our sexual identity:

growth and human development,

masculine/feminine polarities,

male/female biologies,

men’s/women’s gender roles,

techno/economic circumstances,

mind/body distinctions,

victim/perpetrator mentalities,

autonomous/communal drives,

individual/collective pressures, etc.

And though merely having a map does little to free us from our mutual captivity, it at least offers a 50,000 foot view of our psycho-sexual prison — a panopticon of perspectives from which men and women together can devise the ultimate jailbreak, breaking the shackles of oppression and escaping the tyranny of history itself.

Written by Corey W. deVos

Become a member today to listen to this premium podcast and support the global emergence of Integral consciousness

Membership benefits include:

Premium Content

Receive full access to weekly conversations hosted by leading thinkers

Journal Library

Receive full access to the growing Journal of Integral Theory & Practice library

Live Experiences

Stay connected by participating in Integral Life live events and discussions

Courses & Products

Get unlimited 20% discount off all products and courses from our friends and partners

Free Bonus Gifts

Download The Integral Vision eBook by Ken Wilber (worth $19 on Amazon) & The Ken Wilber Biography Series

Support of the movement

Support our mission of educating and spreading integral consciousness that is more critical than at any time in its history

About Vanessa Fisher

Vanessa is a published author, poet and independent scholar.

About Ken Wilber

Ken Wilber is a preeminent scholar of the Integral stage of human development. He is an internationally acknowledged leader, founder of Integral Institute, and co-founder of Integral Life. Ken is the originator of arguably the first truly comprehensive or integrative world philosophy, aptly named “Integral Theory”.